Valparaíso

Valparaíso | |

|---|---|

The historic quarter with the Lutheran Church on the left Cityscape as seen from the sea | |

| Nickname(s): The Jewel of the Pacific, Valpo | |

| Coordinates: 33°02′46″S 71°37′11″W / 33.04611°S 71.61972°W | |

| Country | |

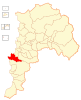

| Region | Valparaíso |

| Province | Valparaíso |

| Founded | 1536 |

| Named for | Valparaíso de Arriba, Spain |

| Capital | Valparaíso |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Mayor | Camila Nieto (FA) |

| Area | |

• City | 401.6 km2 (155.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Population (2017 census)[2] | |

• City | 296,655 |

| • Density | 740/km2 (1,900/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 295,918 |

| • Metro | 951,311 |

| • Rural | 737 |

| Demonym(s) | Porteño (m), Porteña (f) |

| GDP (PPP, constant 2015 values) | |

| • Year | 2023 |

| • Total (Metro) | $28.7 billion[3] |

| • Per capita | $28,500 |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (CLT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−3 (CLST) |

| Area code | (country) 56 + (city) 32 |

| Climate | Csb |

| Website | www |

Valparaíso (Spanish: [balpaɾaˈiso]) is a major city, commune, seaport and naval base facility in Valparaíso Region, Chile.

Greater Valparaíso is the second-most populous city in the country, as well as the second-largest city in the Greater Valparaíso metro area (behind Viña del Mar). Valparaíso was originally named after Valparaíso de Arriba, in Castile-La Mancha, Spain. It is located about 120 km (75 mi) northwest of Santiago, by road, and is one of the Pacific Ocean's most important seaports. Valparaíso is the capital of Chile's second most-populated administrative region and has been the Chilean Navy headquarters since 1817, as well as being the seat of the Chilean National Congress since 1990.

Valparaíso played an important geopolitical role in the second half of the 19th century when it served as a major stopover for ships traveling between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans via the Straits of Magellan. The area experienced rapid growth during its golden age as a magnet for European immigrants, when the city was known by international sailors as "Little San Francisco" and "jewel of the Pacific".[4] Notable developments during this bustling period include Latin America's oldest stock exchange, the continent's first volunteer fire department, Chile's first public library, and the oldest Spanish language newspaper in continuous publication in the world, El Mercurio de Valparaíso. In 2003, the historic quarter of Valparaíso was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The twentieth century was unfavorable to Valparaíso, as many wealthy families abandoned the city. The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, and the associated reduction in ship traffic, dealt a serious blow to the region's shipping- and port-based economy. By the 21st century, the port of San Antonio had surpassed Valparaíso in trade volume (TEU) handled,[5] leading to the questioning of its traditional moniker of Puerto Principal ("principal port") of Chile.[6]

Between the years of 2000 to 2015, the city experienced a recovery, attracting artists, tourists, and cultural entrepreneurs, who settled after they were attracted by the city's hillside historic districts. Today, many thousands of people visit Valparaíso each month, from Chile and abroad, to enjoy the city's labyrinth of cobbled alleys and colorful buildings. The Port of Valparaíso still continues to be a major distribution center for container traffic, copper, and fruit exports. It also receives growing attention from cruise ships that visit during the South American summer. Most significantly, Valparaíso has transformed itself into a major educational and entertainment hub, with four large traditional universities, and several large vocational colleges.

While the city is well-known for its artisans and bohemian culture,[7] it is also famous as the home of several highly-regarded music festivals and other artistic events. The largest, and arguably most iconic, is the annual Viña Del Mar International Song Festival (often simply called "Viña" or "Viña Del Mar"). Typically held in March, in a recently-refurbished, 40,000-capacity amphitheater, "Viña" is one of the biggest annual economic boosts to the region, as the event usually sells-out completely, and thousands of attendees and workers will travel to and stay in the city and metro area. In addition to showcasing numerous performers of many styles, and awarding various prizes, the internationally-televised and live-streamed festival is typically headlined by superstar musicians, from both the Spanish- and English-speaking worlds.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

Some older works starting with Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna (1869) claim that Valparaíso was within the range of the Chango people, but clear evidence for this is lacking.[8]

The Bay of Valparaíso's first ethnically identifiable population were Picunche natives, known for their agriculture. Spanish explorers, considered the first European discoverers of Chile, arrived in 1536, aboard the Santiaguillo, a supply ship sent by Diego de Almagro. The Santiaguillo carried men and supplies for Almagro's expedition, under the command of Juan de Saavedra, who named the town after his native village of Valparaíso de Arriba in Cuenca Province, Spain.

During Spanish colonial times, Valparaíso remained a small village, with only a few houses and a church. On some occasions she was attacked by English pirates and privateers, such as Francis Drake with his ship Golden Hind in 1578[9] and later his cousin Richard Hawkins with his ship Dainty in 1594. Drake's sack of Valparaíso gave origin to the legend about Cueva del Pirata.[10]

In 1810, a wealthy merchant built the first pier in the history of Chile and the first during the colonial era. In its place today, stands the building of El Mercurio de Valparaíso. The ocean then rose to this point. Reclamation of land from the sea moved the coastline five blocks away. Between 1810 and 1830, he built much of the existing port of the city, including much of the land reclamation work that now comprises the city's commercial centre.

In 1814, the naval Battle of Valparaíso was fought offshore of the town, between American and British ships involved in the War of 1812. After Chile's independence from Spain (1818), beginning the Republican Era, Valparaíso became the main harbour for the nascent Chilean navy, and opened international trade opportunities that had been formerly limited to Spain and its other colonies.

Valparaíso soon became a desired stopover for ships rounding South America via the Straits of Magellan and Cape Horn. It gained particular importance supporting and supplying the California Gold Rush (1848–1858). As a major seaport, Valparaíso received immigrants from many European countries, mainly from Britain, Germany, France, Switzerland and Italy. German, French, Italian and English were commonly spoken among its citizens, who founded and published newspapers in these languages.

Valparaíso found maritime competition with Callao (Perú). Both cities sought to be the dominant port on the Pacific Coast of South America during the period of time known as the High Trade (1880–1930). [11]

The British community, La Colonia Britanica, prospered in Valparaíso between the 1820s and 1920s. Firms such as Antony Gibbs & Sons, Duncan Fox, and Williamson-Balfour Company were doing business in the town, which had become a significant trading center by 1840, with 166 British ships, out of a total of 287, anchored in its port. The British settled on Cerro Alegre (Mount Pleasant) and Cerro Concepción. The Association of Voluntary Firemen was created in 1851, a telegraph service to Santiago was operating by 1852, and Chile's first telephone service was set up in 1880. The British Hospital was founded in 1897, and the British Arch, Arco Británico, was erected in 1911. However, by 1895, Italian immigrants exceeded the British, and both the Italians and Germans were in larger numbers by 1907. By 1920, both the Italians and Spanish outnumbered the British, and the primary British community within Chile resided in Santiago.[12]

International immigration transformed the local culture from Spanish origins and Amerindian origins, in ways that included the construction of the first non-Catholic cemetery of Chile, the Dissidents' Cemetery. Football (soccer) was introduced to Chile by English immigrants; and the first private Catholic school in Chile, Le Collège des Sacrés Cœurs ("Sacred Hearts College") and its accompanying Sacred Hearts Church, by French immigrants. Immigrants from Scotland and Germany founded the first private secular schools (The Mackay School and Die Deutsche Schule, respectively). Immigrants formed the first volunteer fire-fighting units (still a volunteer activity in Chile). Their buildings reflected a variety of European styles, making Valparaíso more varied than some other Chilean cities.

On 16 August 1906, a major earthquake struck Valparaíso; there was extensive property damage and thousands of deaths.[13] The Chilean doctor, Carlos Van Buren, of U.S. descent, was involved in the medical care of earthquake victims. He later established the Hospital Carlos Van Buren in 1912.[14]

The golden age of Valparaíso's commerce ended after the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. Shipping shifted to the canal as captains sought to avoid the risks of the Strait of Magellan. The port's use and traffic declined significantly, causing a decline in the city's economy. The opening of the Panama Canal was one of the most critical events in the shaping of Valparaío's economy.[15] Since the turn of the 21st century, shipping has increased in the last few decades with fruit exports, opening the Chilean economy to world commerce, and larger-scale, Post-Panamax ships that do not fit the Panama Canal.

19th century

[edit]

On 28 March 1814, the USS Essex was defeated by British frigates Phoebe and Cherub during the War of 1812, leading to the deaths of 58 US Marines. Captain David Porter, a survivor of this attack, would retire to Portersville, Indiana, and request changing the name to Valparaiso, commemorating the only naval battle he ever lost. By 2 August 1820, the Liberating Expedition of Peru sailed from Valparaíso.

At 10:30 pm on the evening of 19 November 1822, Valparaíso experienced a violent earthquake that left the city in ruins; of the 16,000 residents, casualties included at least 66 adults and 12 children, as well as 110 people wounded. The next day, a meteor trail was visible from Quillota to Valparaíso, seen as a religious experience for much of the population.

In 1826, the Royal Navy Great Britain established a South America Station in Valparaíso to maintain British naval interest in the region. It would remain until 1837, when it was relocated to Esquimalt, British Columbia. 12 September 1827 saw the establishment of El Mercurio de Valparaíso, the oldest circulating newspaper in the Spanish language worldwide.

In May 1828, a constitutional convention began regular meetings in the church of San Francisco. By August 9, the Constitution of the Republic of Chile was fully drafted and disseminated.

On 6 June 1837, Minister Diego Portales was shot at the port outside of Baron Hill on suspicion of promoting conspirators who opposed the Peru-Bolivian Confederation, considered a turning point of Chilean public opinion and the purpose of the war.

By 1851, the first fire brigade in the country was formed. The next year potable running water became available, as well as the first telegraph service in Latin America, between the city and Santiago. It would be another four years before streetlights, with 700 gas lanterns, were installed. In 1861 the first tram company was formed, mostly using horses or mules to draw them, and fully established over the next few years.

In 1852, British shipping company Williamson, Balfour & Cía was established in Valparaíso to handle trade in the region. [16]

Taking advantage of the total lack of defenses, a Spanish fleet commanded by Casto Méndez Núñez bombarded the city during the Chincha Islands War in 1866. Chilean merchant ships were sunk, except for those vessels whose captains hoisted foreign flags.

A merger of the National Steamship Company and Chilean Steamship Company, the South American Steamship Company was created as a national response to the increasing dominance of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company in 1872. In 1880 the Chilean Telephone Company was formed by Americans Joseph Husbands, Peter MacKellar, James Martin, and the US consul Lucius Foot, the first official telephone company in the country. Three years later on the first of December, Concepción funicular opened, the first of many hydraulic systems. After the country's independence and its consequent openness to international trade, Valparaíso became an important port of call on trade routes through the Eastern Pacific. Many immigrants settled there, mostly from Europe and North America, who helped include Valparaíso and Chile in the Industrial Revolution sweeping other parts of the world. This created a different city with civil, financial, commercial and industrial institutions, many of which still exist today.

All this resulted in a population increases. The city reached more than 160,000 inhabitants in the late nineteenth century, making it necessary to use the steep hills for more houses, mansions and even cemeteries. The lack of available land caused the city authorities and developers to reclaim low lying tidal marshland (polders) upon which to build administrative, commercial and industrial infrastructure.

20th century

[edit]

El Mercurio, 1903The Strike of the Seafarers. Fire of the South American Company. Assault on the printing press of El Mercurio. Fire of the Malecon. Attitude of the Authority. The troops arrived from Santiago. The calm is restored. Meetings in the Municipality. It reaches an Arrangement. The Court of Appeals. The city in State of Siege.

The twentieth century began with the first big protest of dockworkers, Chile on 15 April 1903, due to complaints by dockers about their excessive working hours and demands for higher wages, requests that were ignored by employers, creating a tense situation that led to serious violence on 12 May. There were protests and the burning of the CSAV offices and several people were shot and killed. All this prompted intervention by the state. This protest was important for the future of Trade Unionism in the country. That same year, electric trams were introduced.

The 1906 Valparaíso earthquake caused severe damage throughout the city on 16 August, which was at that time the heart of the Chilean economy. The damage was valued at hundreds of millions of pesos of the time, and human victims were counted at 3,000 dead and over 20,000 injured. After the removal of the debris, reconstruction work began. This included the widening of streets, culverting and covering streams, (Jaime and Delicias – creating the avenues Francia and Argentina respectively). The main street of the city (Pedro Montt) was laid and Plaza O'Higgins was created; a hill was removed to allow the passage of Colon Street. The damaged Edwards mansion was demolished and in its place, the present Cathedral of Valparaíso was built and, among many other works, this gave shape to the Almendral Valparaíso area.

In 1910, the port expansion work of the city, which ended in 1930, began. A long breakwater was built, along with piers and docking terminals.

The Imperial German East Asia Squadron engaged the British West Indies Squadron on 1 November 1914 at the Battle of Coronel off the coast of Valparaiso, sinking two British cruisers. After the battle the East Asia Squadron stayed in Valparaiso Harbor before continuing to the Falklands.

21st century

[edit]

Chile's legislature along with other institutions of national importance like the National Customs Service, the National Fish and Aquaculture Ministry, the Ministry of Culture and the Barracks General of the Chilean Navy are sited in the city. In addition to the capital of the Valparaíso Region hosts the Regional Administration and government.

In 2003, Valparaíso became an UNESCO World Heritage Centre. This title was awarded to Valparaiso for its unique urban form, as well as its clear maintained historical background as a colorful port city. In becoming a World Heritage Center, Valparaíso is tasked with maintaining its cultural heritage, through the maintenance of its historic infrastructure, like its Ascensores.

On 13 April 2014, a huge brush fire burned out of control, destroying 2,800 homes and killing 16 people, forcing President Michelle Bachelet to declare it a disaster zone.[17]

In early February 2024, a huge brush fire burned through Valparaiso and central Chile, killing at least 131 people.[18]

Geography

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

Valparaíso is located in central Chile, 120 km (75 mi) to the north west of the capital Santiago. Valparaíso, like most of Chile, is vulnerable to earthquakes. Before the earthquake of February 27, 2010, which measured 8.8 on the moment magnitude scale,[19] the last catastrophic earthquake to strike Valparaíso devastated the city in August 1906, killing nearly 3,000 people.[20] Other significant earthquakes to affect the city were the 1730 Valparaíso earthquake and the 1985 Algarrobo earthquake.

Geology

[edit]Because of Valparaíso's proximity to the Peru–Chile Trench, the city is vulnerable to earthquakes. The Peru–Chile Trench stores large amounts of energy for a very long time and sometimes ruptures after short intervals in a violent earthquake.

Climate

[edit]Valparaíso has a very mild Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csb). The summer is essentially dry, but the city is affected by fogs from the Humboldt Current during most of the year. In the winter, rainfall can occasionally be extremely heavy when a powerful frontal system crosses central Chile, but frequency of such rains varies greatly from year to year. Monthly average temperatures vary just around 6°C between the coolest and the warmest month, from 17 °C (63 °F) in January to 11.4 °C (52.5 °F) in July. Snowfall occurs rarely in the highest parts of the city. In winter, strong winds can lead to wind chill temperatures below freezing.[citation needed]

| Climate data for Valparaíso, Chile (Punta Angeles Lighthouse, located at Playa Ancha University) 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1970–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.8 (85.6) |

31.2 (88.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.4 (83.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.2 (86.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.9 (71.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

17.9 (64.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.6 (56.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

9.9 (49.8) |

8.6 (47.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9.8 (49.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

6.8 (44.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

2.0 (35.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

1.9 (35.4) |

4.6 (40.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

1.6 (34.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.2 (0.01) |

1.2 (0.05) |

2.8 (0.11) |

14.9 (0.59) |

66.2 (2.61) |

106.1 (4.18) |

66.7 (2.63) |

61.2 (2.41) |

24.9 (0.98) |

12.7 (0.50) |

3.8 (0.15) |

2.5 (0.10) |

363.2 (14.30) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 24.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 79 | 78 | 75 | 71 | 70 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 279.0 | 245.7 | 217.0 | 174.0 | 114.7 | 81.0 | 93.0 | 117.8 | 147.0 | 170.5 | 216.0 | 263.5 | 2,119.2 |

| Source 1: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile (humidity 1931–1960)[21][22][23] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate & Temperature (sunshine hours),[24] NOAA (precipitation days 1991–2020)[25] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Valparaíso (Rodelillo Airfield) 1991–2020, extremes 1975–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.6 (94.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

29.2 (84.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.9 (89.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

34.9 (94.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 12.4 (54.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

11.7 (53.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.9 (46.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

2.0 (35.6) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

1.1 (34.0) |

2.4 (36.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.7 (0.03) |

1.1 (0.04) |

3.9 (0.15) |

20.4 (0.80) |

96.0 (3.78) |

161.7 (6.37) |

89.3 (3.52) |

88.7 (3.49) |

37.9 (1.49) |

15.5 (0.61) |

5.0 (0.20) |

3.7 (0.15) |

523.9 (20.63) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 26.7 |

| Source 1: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile[26][27] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (precipitation days 1991–2020)[28] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

[edit]| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Cerro Concepción | |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii |

| Reference | 959 |

| Inscription | 2003 (27th Session) |

| Area | 23.2 ha |

| Buffer zone | 44.5 ha |

Nicknamed "The Jewel of the Pacific", Valparaíso was declared a world heritage site based upon its improvised urban design and unique architecture. In 1996, the World Monuments Fund declared Valparaíso's unusual system of funicular lifts (steeply inclined carriages) one of the world's 100 most endangered historical treasures. In 1998, grassroots activists convinced the Chilean government and local authorities to apply for UNESCO world heritage status for Valparaíso. Valparaíso was declared a World Heritage Site in 2003. Built upon dozens of steep hillsides overlooking the Pacific Ocean, Valparaíso has a labyrinth of streets and cobblestone alleyways, embodying a rich architectural and cultural legacy. Valparaíso is protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Since its status as a World Heritage Site, Valparaíso has made several changes to its urban fabric in the process of maintaining its cultural heritage.

Landmarks include:

- Iglesia de la Matriz

- Plaza Aníbal Pinto

- Plaza Sotomayor including the Edificio Armada de Chile

- Edificio Luis Cousiño

- Courthouse

- 16 remaining funiculars (called ascensores): 15 public (national monuments) and 1 private (which belongs to "Hospital Carlos Van Buren").[29]

- The Concepcion and Alegre historical district

- The Bellavista hill, which has the "Museo a Cielo Abierto" or "open air museum"

- Monument to Admiral Lord Thomas Alexander Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald

- Monument to Manuel Blanco Encalada, first Chilean President

- Capilla del Carmen

- Cemeteries on Panteón Hill – Cemetery Number One (Catholic) and Dissidents Cemetery (Protestant)

Gallery

[edit]

Demographics

[edit]Although technically only Chile's sixth largest city, with an urban area population of 295,918 (296,655 in municipality[2]), the Greater Valparaíso metropolitan area, including the neighbouring cities of Viña del Mar, Concón, Quilpué and Villa Alemana, is the second largest in the country (951,311 inhabitants).

According to the 2017 census of the National Statistics Institute, the commune of Valparaíso spans an area of 401.6 km2 (155 sq mi) and has 296,655 inhabitants (144,945 men and 151,710 women). Of these, 295,918 (99.8%) lived in urban areas and 737 (0.2%) in rural areas. The population grew by 7.49% (20,673 persons) between the 2002 and 2017 censuses.[2]

Residents of Valparaíso are commonly called porteños (feminine: porteñas), spanish for "port dweller".[30][31]

Government

[edit]As a commune, Valparaíso is a third-level administrative division of Chile administered by a municipal council, headed by an alcalde (mayor) who is directly elected every four years. For the 2024–2028 term, the mayor is Camila Nieto Hernández (FA). The communal council has the following members:[1]

- Leonardo Contreras Neira (RN)

- Miguel Vergara González (REP)

- Valentina Véliz González (REP)

- Dante Iturrieta Méndez (UDI)

- Jorge López Morales (PDG)

- Alicia Zúñiga Valencia (PCCh)

- Lukas Cáceres Costa (FA)

- Thelmo Aguilar Rojas (Ind./FA)

- Vicente Celedón Collao (Ind./FRVS)

- Jazmin Murillo Jorquera (Ind./PPD)

Within the electoral divisions of Chile, Valparaíso is represented in the Chamber of Deputies by Andrés Celis (RN), Hotuiti Teao (Ind./EVOP), Luis Sánchez (REP), Tomás Lagomarsino (PR), Tomás de Rementería (PS), Camila Rojas (FA), Jorge Brito (FA), and Luis Cuello (PCCh) for the 2022–2026 term, as part of the 7th electoral district, together with Juan Fernández, Isla de Pascua, Viña del Mar, Concón, Algarrobo, Cartagena, Casablanca, El Quisco, El Tabo, San Antonio, and Santo Domingo. In the Senate, the commune is represented by Francisco Chahuán (RN), Kenneth Pugh (RN), Isabel Allende (PS), Juan Latorre (FA), and Ricardo Lagos Weber (PPD) for the 2018–2026 term, as part of the 6th senatorial constituency (Valparaíso Region).

The Chilean Congress meets in a modern building in the Almendral section of Valparaíso, after relocation from Santiago during the last years of the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. Although congressional activities were to be legally moved by a ruling in 1987, the newly built site only began to function as the seat of Congress during the government of Patricio Aylwin in 1990.

Economy

[edit]

Major industries include tourism, culture, shipping and freight transport.

Approximately 50 international cruise ships call on Valparaíso during the 4-month Chilean summer. The port of Valparaíso is also an important hub for container freight and exports many products, including wine, copper, and fresh fruit.

Transport

[edit]

A commuter rail service, the Valparaíso Metro, opened to the public on 24 November 2005. The creation of this system involved updating parts of the Valparaíso-Santiago Railway, originally built in 1863. The Valparaíso Metro constitutes the so-called "fourth stage" ("Cuarta Etapa") of Metropolitan improvements. The Metro now connects the city core of Valparaíso with Viña del Mar and other cities. It extends along most of Gran Valparaíso, and is the second underground urban rail system in operation in Chile (after Santiago's), as it includes a tunnel section that crosses Viña del Mar's commercial district. The proposed Santiago–Valparaíso railway line would link Valparaíso and Santiago in around 45 minutes.

Public transport within Valparaíso itself is provided primarily by buses, trolleybuses and funiculars. The buses provide an efficient and regular service to and from the city centre and the numerous hills where most people live, as well as to neighbouring towns while more distant towns are served by long-distance coaches. Buses are operated by several private companies and regulated by the Regional Ministry of Transport, which controls fares and routes.[32] The Valparaíso trolleybus system has been in operation since 1952, and in 2019 it continues to use some of its original vehicles, built in 1952 by the Pullman-Standard Company, along with an assortment of other vehicles acquired later.[33][34][35] Some of Valparaíso's Pullman trolleybuses are even older, built in 1946–48, having been acquired secondhand from Santiago in the 1970s. The surviving Pullman trolleybuses are the oldest trolleybuses still in normal service anywhere in the world,[32][36] and they were collectively declared National Historic Monuments by the Chilean government in 2003.[32][37]

Valparaíso's road infrastructure has been undergoing improvement, particularly with the completion of the "Curauma — Placilla — La Pólvora" freeway bypass,[38] which will allow trucks to go directly to the port facility over a modern highway and through tunnels, without driving through the historic and already congested downtown streets. In addition, roads to link Valparaíso to San Antonio, Chile's second-largest port, and the coastal towns in between (Laguna Verde, Quintay, Algarrobo, and Isla Negra, for example), are also under construction. Travel between Valparaíso and Santiago takes about 80 minutes via a modern toll highway.

Internal passenger air services to Valparaíso are provided through the airport at Quintero which is some distance from the city but now served by good roads. The great majority of foreign visitors arrive through Santiago or on cruise liners.

Funiculars

[edit]Because of the slopes of the hills, many of the surrounding areas of Valparaíso are inaccessible by public transport. That is why "elevators" serve the function of communicating the high part of the city with the plan, besides being a strong holiday highlight. The only elevator that can truly be called as such, is the Ascensor Polanco, because it is vertical. Meanwhile, the rest are cable cars but traditionally called elevators. Several of those funiculars – locally called ascensores – provide public transport service between the central area and the lower slopes of the surrounding hills,[32] the first of which (Ascensor Concepción, also known as Ascensor Turri) opened in 1883, operated by steam, is still in service.[39][40][41] The Cerro Cordillera elevator was built in 1887. As many as 28 different funicular railways have served Valparaíso at one time or another, of which 14 were still in operation in 1992[40] and still around 12 in 2010.

Valparaíso has fifteen lifts declared Historical Monuments by the National Monuments Council. Five are municipal property and the remaining belong to four private companies. The elevators are elevators municipal Baron, El Peral, Polanco, Queen Victoria and St. Augustine. As for the rest, lifts Florida, Butterflies and Nuns are owned by the National Elevator Company SA; Artillery, Concepción and Mountains belong to the Society of Mechanical Lifts Valparaíso Holy Spirit, Larraín and Villaseca (stopped for repairs) are the property of Valparaíso Elevators Company SA, and Dairy (stopped by fire) belongs to the Society of Dairy Cerro Lifts Ltd.

As a part of its 2003 declaration as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Valparaíso has promised to replace and maintain its several funiculars. The funiculars were identified as an important cultural artifact.

Valparaíso public transportation statistics

[edit]The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Valparaíso and Viña del Mar, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 68 min. 15% of public transit riders, ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 13 min, while 15% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 7 km, while 12% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[42]

Port of Valparaíso

[edit]The port of Valparaíso is divided into ten sites which sites 1,2,3,4 and 5 are administered by South Pacific Terminal SA and sites 6,7,8,9 and 10 for Valparaíso Port Company. The last two sites include a dock and are used as public walks and cruise passenger terminal.

Valparaíso is the main container and passenger port in Chile, transferring 10 million tons annually, and serves about 50 cruises and 150,000 passengers.

Culture

[edit]

During Valparaíso's golden age (1848–1914), the city received large numbers of immigrants, primarily from Europe.[43] The immigrant communities left a unique imprint on the city's noteworthy architecture. Each community built its own churches and schools, while many also founded other noteworthy cultural and economic institutions. The largest immigrant communities came from Britain, Germany, and Italy, each developing their own hillside neighbourhood, preserved today as National Historic Districts or "Zonas Típicas".

During the second half of the 20th century, Valparaíso experienced a great decline, as wealthy families de-gentrified the historic quarter, moving to bustling Santiago or nearby Viña del Mar. By the early 1990s, much of the city's unique heritage had been lost and many Chileans had given up on the city. But in the mid-1990s, a grassroots preservation movement blossomed in Valparaíso where nowadays also a vast number of murals created by graffiti artists can be viewed on the streets, alleyways and stairways.

The Fundación Valparaíso (Valparaíso Foundation), founded by the North American poet Todd Temkin, has executed major neighborhood redevelopment projects; has improved the city's tourist infrastructure; and administers the city's jazz, ethnic music, and opera festivals; among other projects. Some noteworthy foundation projects include the World Heritage Trail,[44] Opera by the Sea,[45] and Chile's "Cultural Capital".[46] During recent years, Mr. Temkin has used his influential Sunday column in El Mercurio de Valparaíso to advocate for many major policy issues, such as the creation of a "Ley Valparaíso" (Valparaíso Law) in the Chilean Congress, and the possibility that the Chilean government must guarantee funding for the preservation of Valparaíso's beloved funicular elevators.

Valparaíso's newspaper, El Mercurio de Valparaíso is the oldest Spanish-language newspaper in circulation in the world.

The Fundacion LUKAS maintains the drawings and paintings of the cartoonist Renzo Antonio Giovanni Pecchenino Raggi (stage name LUKAS),[49] who came to symbolize Valparaíso in popular culture, in a new restored building overlooking the bay.[50]

Valparaíso is also home to the so-called "School of Valparaíso", which is in fact the Faculty of Architecture & Urbanism of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso. The "School of Valparaíso" was in the 1960s and 1970s one of the most experimental, avant-garde and controversial Architectural schools in the country.

Valparaíso stages a major festival attended by hundreds of thousands of participants on the last three days of every year. The festival culminates with a "New Year's by the Sea" fireworks show, the biggest in all of Latin America, attended by a million tourists who fill the coastline and hillsides with a view of the bay. Even though everyone calls it the Valparaíso Fireworks, it is, in fact, a fireworks display running along a great part of the coast from Valparaíso, past Viña del Mar and all the way to Concón.

In 2003, the Chilean Congress declared Valparaíso to be "Chile's Cultural Capital" and home for the nation's new cultural ministry.

Valparaíso offers various urban nightlife activities. Traditional bars and nightclubs can be found near Plaza Sotomayor. A vivid guide to Valparaíso can be found in the novels of Cayetano Brule, the private detective who lives in a Victorian house in the picturesque Paseo Gervasoni in Cerro Concepción.

Health system

[edit]The public healthcare system mainly relies on the Hospital Carlos Van Buren located at the plan and Hospital Valparaíso (officially Hospital Eduardo Pereira) located at St. Roque Hill. There are also several clinics like Universidad de Chile's Clinica Barón, Hospital Aleman (due to close), and the former Naval Hospital on Playa Ancha Hill.

Sports

[edit]Valparaíso has several public sports venues and facilities, including a growing network of cycle routes.[51]

- The Club Deportivo Playa Ancha (Playa Ancha Sports Club), located in Av. Playa Ancha 451, Cerro Playa Ancha,[52] opened in 1919 and offers football pitches, table football, basketball and tennis courts, two swimming pools and a small gym. Tennis and swimming lessons are held in the club as well as local tournaments, and the pool can be used recreationally in summer.

- The Complejo Deportivo Escuela Naval (Naval School Sports Centre), located at General Hontaneda, Cerro Playa Ancha,[53] offers Olympic-standard modern facilities with a heated swimming pool and indoor volleyball, basketball, gymnastics, judo and fencing areas. It also has extensive outdoor sports facilities, suitable for rugby, football and tennis.

- The Estadio Elías Figueroa Brander (formerly Chiledeportes Regional Stadium) is located at the junction of Hontaneda and Subida Carvallo, Cerro Playa Ancha,[54] This stadium has historic links to the local football team, Santiago Wanderers, the oldest professional football team in Chile founded on August 15, 1892. Built in 1931, it holds 18,500 people[55] and also serves as an athletics and swimming venue.

- Fortín Prat (Fort Prat), located at Rawson 382, Almendral,[56] is a historic basketball venue, hosting the "golden age" of Valparaíso basketball from 1950 to 1970. Fort Prat has also hosted numerous local handball, table tennis and boxing championships. It offers children's classes and a gym, and is also home to the Valparaíso Basketball Association Museum.

- The Muelle Deportivo Curauma is located 20 minutes from Valparaíso in Lake Pañuelas at Avenue Borde Laguna and Curauma.[57] The calm waters of the 195 km2 lagoon permits rowing, kayaking, fishing and boating. It has also been chosen as a venue for the 2014 South American Games. Around the lagoon are camping sites, cycle and hiking trails, and paintball and canopy facilities.[58]

- The Puerto Deportivo Valparaíso,[59] located at Muelle Barón, Bordemar Centro,[60] is a watersports centre which offers sailing, kayaking and scuba diving lessons and hosts the "Valpo Sub" program that seeks to preserve the area's underwater heritage, offering educational tours and expeditions to shipwrecks along the bay. Puerto Deportivo Valparaíso also carries out programs promoting ecotourism in Valparaíso Bay, and rents equipment for people having lessons. It features an interactive room that shows information on the underwater heritage.

- The Velódromo Roberto Parra[61] is located opposite the Club Deportivo Playa Ancha and is part of its wider complex. The velodrome contains a cycle track, table football, and handball and basketball courts. All its facilities are available for public rent.

Valparaíso was one of the host cities of the official 1959 Basketball World Cup, where Chile won the bronze medal.

The "Valparaíso Downhill"[62] is a mountain bike race that takes place in February. Riders race through the city streets tackling the steps and alleys, finding their own way through the ramps and jumps down to the "plan" (Valparaíso's "lowlands"). The Valparaíso Downhill has been described by Chop MTB as "the craziest urban downhill race of all".[63]

Since 2005, a series of running events has taken place in the city with 5 km, 10 km, 21 km and marathon distances. The race starts at Muelle Barón and the course runs along the seafront, crossing diverse architectural and geographical landmarks.[64]

The final stage of the 2014 Dakar Rally ended up at Valparaíso's Plaza Sotomayor in the heart of the old town, surrounded by historic buildings. Ignacio Casale, the Chilean winner of the 2014 Quad category, was cheered here in the streets by the Valparaíso crowd.[65]

Education

[edit]Educational establishments

[edit]At primary school level, Valparaíso boasts some of the most emblematic schools in the region, such as the Liceo Eduardo de la Barra and Salesian College Valparaíso. Other landmarks of the city schools are the Mary Help of Christians School, San Rafael Seminary, the Lycée Jean d'Alembert, Colegio San Pedro Nolasco, Scuola Italiana Arturo Dell' Oro and Deutsche Schule Valparaíso, among others. Many of the schools named in the plan are located directly in the city, especially in the Almendral neighborhood.[66]

In addition, Valparaíso was the birthplace of many private schools founded by the European colonies, as the German School, the Alliance Francaise, Mackay College (now located in the neighboring resort of Viña del Mar) and the College of the Sacred Hearts of Valparaíso, that operating since 1837 is the oldest private school in South America.

University establishments

[edit]Valparaíso has many institutions of higher education, including some of the most important universities of Chile, called "traditional universities", like the Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso, the University of Valparaíso, the Playa Ancha University and the Federico Santa María Technical University. The main building of this last is visible from much of the city, as it is located on the front of the hill 'Cerro Placeres', and has characteristic Tudor Gothic and Renaissance architecture. The city has many nontraditional colleges of varying size, quality and focus.[67]

| University | Foundation | Acronym | Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Federico Santa María Technical University | 1931 | UTFSM/USM | Private university

Traditional |

|

Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso | 1925 | UCV/PUCV | Private university

Traditional |

|

Playa Ancha University of Educational Sciences | 1948 | UPLA | Public university |

|

University of Valparaíso | 1981 | UV | Public university |

Notable residents

[edit]Valparaíso is the birthplace of many historically significant figures, including:

- Abelardo Quinteros, Chilean composer

- Augusto Pinochet, general and dictator of Chile

- Camilo Mori, Chilean painter

- Esteban Orlando Harrington, Chilean architect

- Matias Novoa, Chilean-Mexican actor

- Claudio Naranjo, Chilean psychiatrist

- Chris Watson, Australia's third Prime Minister, and the first Australian Labour Prime Minister

- Curt Echtermeyer, also known as Curt Bruckner (1896–1971), German painter

- Percy John Daniell, English mathematician

- Marsia Alexander-Clarke, American artist[68]

- Roberto Ampuero, author of the internationally published novels about the private eye Cayetano Brulé and "Hijo Ilustre" of Valparaíso, Foreign Minister of Chile

- Giancarlo Monsalve, Chilean international opera singer, Cultural Ambassador of Valparaíso and UNESCO medal[69][70][71]

- Sergio Badilla Castillo, Chilean poet, founder of poetic transrealism in contemporary poetry

- Ernestina Pérez Barahona, Chilean physician

- Elvira Santa Cruz Ossa, Chilean dramatist and novelist

- Alicia Herrera Rivera, feminist lawyer, minister of the Court of Appeals of Santiago

- Juana López (nurse), Chilean army nurse

- J. G. Robertson, English singer and actor

- José Maza Sancho, Chilean astronomer

- Sergio Larraín, Chilean photographer

It has also been the residence of many writers such as the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío and the American poet Marion Manville Pope.

Puerto Rican pro-independence leader Segundo Ruiz Belvis died in the city in November 1867.

- Jorge Dip, lawyer and politician, governor of the province of Valparaíso

Religion

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2023) |

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Valparaíso is twinned with:[72]

Badalona, Spain

Badalona, Spain Barcelona, Spain

Barcelona, Spain Bat Yam, Israel

Bat Yam, Israel Busan, South Korea

Busan, South Korea Callao, Peru

Callao, Peru Córdoba, Argentina

Córdoba, Argentina Guangzhou, China

Guangzhou, China Havana, Cuba

Havana, Cuba Long Beach, United States

Long Beach, United States Malacca, Malaysia

Malacca, Malaysia Manzanillo, Mexico

Manzanillo, Mexico Medellín, Colombia

Medellín, Colombia Novorossiysk, Russia

Novorossiysk, Russia Oviedo, Spain

Oviedo, Spain Rosario, Argentina

Rosario, Argentina Salvador, Brazil

Salvador, Brazil Santa Fe, Spain

Santa Fe, Spain Shanghai, China

Shanghai, China Veracruz, Mexico

Veracruz, Mexico

Partnerships

[edit]Valparaíso cooperates with:[72]

Basel, Switzerland

Basel, Switzerland Odesa, Ukraine

Odesa, Ukraine San Francisco, United States

San Francisco, United States

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Mayor and Council". Municipality of Valparaíso (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 September 2024. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Resultados CENSO 2017". National Statistics Institute of Chile (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ "TelluBase—Chile Fact Sheet (Tellusant Public Service Series)" (PDF). Tellusant. Retrieved 2024-01-11.

- ^ Between Two Worlds: Memoirs of a Philosopher-Scientist ISBN 978-3-319-29250-2 p. 120

- ^ "Valparaíso sube dos puestos y San Antonio se mantiene TOP 10 en ránking de puertos de Cepal". PortalPortuario.cl (in Spanish). 2018-05-28. Archived from the original on 2022-04-12. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ^ "Mensaje de Jorge Sharp en Twitter generó disputa por título de "puerto principal" entre San Antonio y Valparaíso". SoyChile (in Spanish). 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-08-26. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ^ Payá G., Ernesto (2011). "Valparaíso: la vieja y nueva bohemia" [Valparaiso: new and old bohemia]. Revista chilena de infectología (in Spanish). 28 (3): 229. doi:10.4067/S0716-10182011000300005. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- ^ Vera Villarroel, Jaime (6 December 2018). "Los changos, su supuesta presencia en la bahía de Valparaíso". Boletín Histórico (in Spanish). VII (XXII): 79–103. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Sugden, John (2012). Sir Francis Drake. Random House. p. 125. ISBN 9781448129508.

- ^ Montecino Aguirre, Sonia (2015). Mitos de Chile: Enciclopedia de seres, apariciones y encantos (in Spanish). Catalonia. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-956-324-375-8.

- ^ Couyoumdjian, Juan Ricardo (2000). "El Alto Comercio de Valparaiso y las Grandes Casas Extranjeras, 1880-1930: Una Aproximacion". Historia (Santiago). 33: 63–99. doi:10.4067/S0717-71942000003300002. ISSN 0717-7194. Archived from the original on 2023-03-10. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Edmundson, William (2009). A History of the British Presence in Chile: From Bloody Mary to Charles Darwin and the Decline of British Influence. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 110–115. ISBN 9780230114838.

- ^ "Valparaiso, Chile 1906: M 8.2 – Valparaiso, Chile". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "The Van Buren Hospital in the history of Chile". hekint.org. 13 April 2014. Archived from the original on 20 July 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Shaping Terrain: City Building in Latin America. University Press of Florida. 2016. doi:10.2307/j.ctvx1ht3b. JSTOR j.ctvx1ht3b. Archived from the original on 2023-03-10. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Couyoumdjian, Juan Ricardo (2000). "El Alto Comercio de Valparaiso y las Grandes Casas Extranjeras, 1880-1930: Una Aproximacion". Historia (Santiago). 33: 63–99. doi:10.4067/S0717-71942000003300002. ISSN 0717-7194. Archived from the original on 2023-03-10. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ "Chile declares disaster as deadly fire storms historic port city". BusinessLIVE. 13 April 2014. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Villegas, Alexander (6 February 2024). "Chileans Search Rubble for Wildfire Victims as Death Toll Rises to 131". U.S. News. Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Soto, Alonso (2010-02-27). "Massive earthquake hits Chile, 122 dead". Yahoo! News. Reuters. Archived from the original on 2010-03-05. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ^ Martland, Samuel. 2007. "Reconstructing the City, Constructing the State: Government in Valparaíso after the Earthquake of 1906", Hispanic American Historical Review 87, no. 2: 221–254. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed September 13, 2008)

- ^ "Datos Normales y Promedios Históricos Promedios de 30 años o menos" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ "Temperaturas Medias y Extremas en 30 Años-Entre los años: 1991 al 2020-Nombre estación: Punta Ángeles faro" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ "Temperatura Histórica de la Punta Ángeles faro (330002)" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ "Valparaíso Climate Guide to the Average Weather & Temperatures with Graphs Elucidating Sunshine and Rainfall Data & Information about Wind Speeds & Humidity". Climate & Temperature. Archived from the original on 2011-11-26. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- ^ "Faro Punta Angeles Valparaiso Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ "Datos Normales y Promedios Históricos Promedios de 30 años o menos" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "Temperatura Histórica de la Estación Rodelillo, Ad. (330007)" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "Rodelillo Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ See also Funicular railways of Valparaíso for the range of total numbers and active numbers, given from different sources.

- ^ Gregory, Vanessa (November 8, 2009). "Tastes of Newly Fashionable Valparaíso, Chile". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2010-11-23. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- ^ Gabanski, Pepa (21 January 2011). "Old Prejudices Die Hard In Chile's Rival Coastal Cities: Viña and Valparaíso". The Santiago Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d Webb, Mary (ed.) (2009). Jane's Urban Transport Systems 2009–2010, pp. 65–66. Coulsdon (UK): Jane's Information Group. ISBN 978-0-7106-2903-6.

- ^ Trolleybus Magazine No. 344 (March–April 2019), p. 68. ISSN 0266-7452.

- ^ The Trolleybuses of Valparaíso, Chile Archived 2019-04-12 at the Wayback Machine (detailed history). Allen Morrison. 2006. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ Ossandón, Javier (1 April 2014). "Diez trolebuses de origen suizo modernizarán la flota porteña" [Ten trolleybuses from Switzerland modernize the Valparaíso fleet]. El Mercurio (in Spanish). p. 8. Archived from the original on 2017-07-01. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- ^ Trolleybus Magazine No. 281 (September–October 2008), p. 110. ISSN 0266-7452.

- ^ "Quince troles porteños so monumentos históricos (15 Valparaíso trolleys are historic monuments)". La Estrella (in Spanish). 29 July 2003. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- ^ ""Curauma — Placilla — La Pólvora"". Archived from the original on 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ^ Paredas R., Alexis (4 April 2019). "El ascensor más antiguo del Puerto reabre con marcha blanca y gratuito" [The oldest funicular in Valparaíso reopens with commissioning and free service]. El Mercurio (in Spanish). p. 4. Archived from the original on 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ a b Morrison, Allen (1992). The Tramways of Chile Archived 2019-06-03 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 31–32. New York: Bonde Press. ISBN 0-9622348-2-6.

- ^ Ascensor Concepción Archived 2013-09-25 at the Wayback Machine (Spanish). Capital Cultural. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- ^ "Valparaíso y Viña del Mar Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ "Immigration". This is Chile. 2014-03-11. Archived from the original on 2019-02-21. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- ^ "Sendero Bicentenario". Archived from the original on 2004-08-05. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

- ^ "Ópera en el Mar". Archived from the original on 2006-10-21. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

- ^ AyerViernes S.A. "Capital Cultural". Capitalcultural.cl. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ^ PCdV – Historical Review Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. pcdv.cl

- ^ Webb, Michael (2012-10-24). "Open City: Ex Cárcel Parque Cultural by HLPS in Valparaíso, Chile". Architectural Review. Archived from the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ "Fundacion LUKAS". 2002-05-23. Archived from the original on 2002-05-23. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ "Cerro Concepcion Valparaiso, Chile". 2009-08-13. Archived from the original on 2009-08-13. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Cycle rout Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine ciudaddevalparaiso.cl retrieved on February 07, 2014

- ^ Club Deportivo Playa Ancha (Playa Ancha sports club) Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine ciudaddevalparaiso.cl retrieved February 07, 2014

- ^ Complejo Deportivo Escuela Naval (Navy School Sports Centre) Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine ciudaddevalparaiso.cl retrieved February 07, 2014

- ^ "Estadio Regional Chiledeportes". 2014-03-06. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ "Stadiums in Chile". Worldstadiums.com. Archived from the original on 2001-12-02. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- ^ Fortín Prat (Fort Prat) Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine ciudaddevalparaiso.cl retrieved February 07, 2014

- ^ Muelle Deportivo Curauma Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine ciudaddevalparaiso.cl retrieved February 07, 2014

- ^ Ecoturismo Peñuelas Archived 2014-02-26 at the Wayback Machine www.lagopenuelas.com retrieved February 08, 2014

- ^ "Arriendos | Puerto Deportivo Valparaíso | Región de Valparaíso". Puertodeportivo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Puerto Deportivo Valparaíso Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine ciudaddevalparaiso.cl retrieved February 07, 2014

- ^ Velódromo Roberto Parra Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine ciudaddevalparaiso.cl retrieved February 07, 2014

- ^ "Downhill bike race in Chile is insanity at its finest". Gadling. 2011-03-03. Archived from the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Valparaíso – still the craziest urban downhill race of them all! Archived 2014-02-27 at the Wayback Machine chopmtb.com/ JCW, FEBRUARY 25, 2013 retrieved on

- ^ "Maratón de Valparaiso 2022 - Sitio Oficial". Maratón de Valparaiso. Archived from the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ Minuto a Minuto El Rally Dakar 2014 llega a su fin en Valparaíso Archived 2014-02-23 at the Wayback Machine www.24horas.cl/ ALONSO SÁNCHEZ MONCLOA January 18, 2014, retrieved on February 08, 2014

- ^ "Escuelas y liceos" (in Spanish). Corporación Municipal Valparaíso. 25 May 2018. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ "Universidades de Valparaíso (Privadas y Estatales Públicas)". altillo.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Marsia Alexander-Clarke (2003). "Marsia Alexander-Clarke, Video Artist". Archived from the original on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ^ "El Mercurio". Mercuriovalpo.cl. 2010-08-04. Archived from the original on 2012-04-23. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ^ "deslumbra a Europa". Estrellavalpo.cl. 2010-08-04. Archived from the original on 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ^ "24 Horas – Tenor Giancarlo Monsalve visita Valparaíso". 24horas.cl. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ^ a b "Ciudades Hermanas". vregion.cl (in Spanish). Región de Valparaíso. Archived from the original on 2020-06-08. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

External links

[edit]- Municipality of Valparaíso (in Spanish)

- El Mercurio de Valparaíso—Main newspaper (in Spanish)

- The Concepcion and Alegre historical district

- Valparaíso

- 1536 establishments in South America

- 1536 establishments in the Spanish Empire

- Capitals of Chilean provinces

- Capitals of Chilean regions

- Communes of Chile

- Populated coastal places in Chile

- Populated places established in 1536

- Populated places in Valparaíso Province

- Port cities in Chile

- World Heritage Sites in Chile